Understanding Causality for Social Changemakers: A Framework for Deep Systems Engagement

035. Distinguishing between causal conditions, causal mechanisms, causal powers, and causal capacities.

In many spheres of human understanding—particularly in Western intellectual traditions—causality has long been conceptualised in linear terms. The dominant model follows a straightforward logic: cause A produces effect B. This linear view aligns with the classical scientific method, where variables are isolated, hypotheses are tested under controlled conditions, and causality is inferred through patterns of regular association. While this model has yielded immense benefits in certain domains (notably in the physical sciences), its application to the complexities of social life can be profoundly limiting.

Social systems—by their very nature—are dynamic, context-dependent, and shaped by multiple, interrelated forces. For changemakers engaging in efforts to transform communities, dismantle inequities, or build peace, a linear model of causality often fails to account for the non-linearity, feedback loops, and emergent properties that characterise the systems in which they operate. As such, developing a more nuanced and systemic understanding of causality is not only intellectually sound—it is essential for designing effective interventions and fostering sustainable impact.

The Limitations of Linear Causality in Social Change

Linear causal thinking tends to assume direct, one-directional relationships between inputs and outcomes. This model is appealing for its simplicity and clarity. It lends itself to logic models, strategic plans, and evaluation frameworks that demand measurable outputs and predictable timelines. However, in the realm of social change—whether addressing gender-based violence, climate injustice, intergenerational poverty, or political exclusion—such assumptions often fall short.

Social phenomena are shaped by a web of intersecting causal influences. Interventions rarely produce the same outcomes in different contexts because outcomes are contingent upon existing systems, histories, power relations, and collective meaning-making. Moreover, social interventions may have unintended consequences, delayed effects, or create ripple effects across domains in ways that linear models cannot anticipate or explain.

A linear frame might suggest, for instance, that increasing school enrolment directly leads to improved educational outcomes. But a more accurate understanding would consider the mediating role of teacher quality, curriculum relevance, gender norms, household income, language, food security, and psychosocial support—all of which are causal conditions that shape how, and whether, an intervention will succeed.

Using Multidimensional ‘Causal Structure’ to Understand Complex Causality

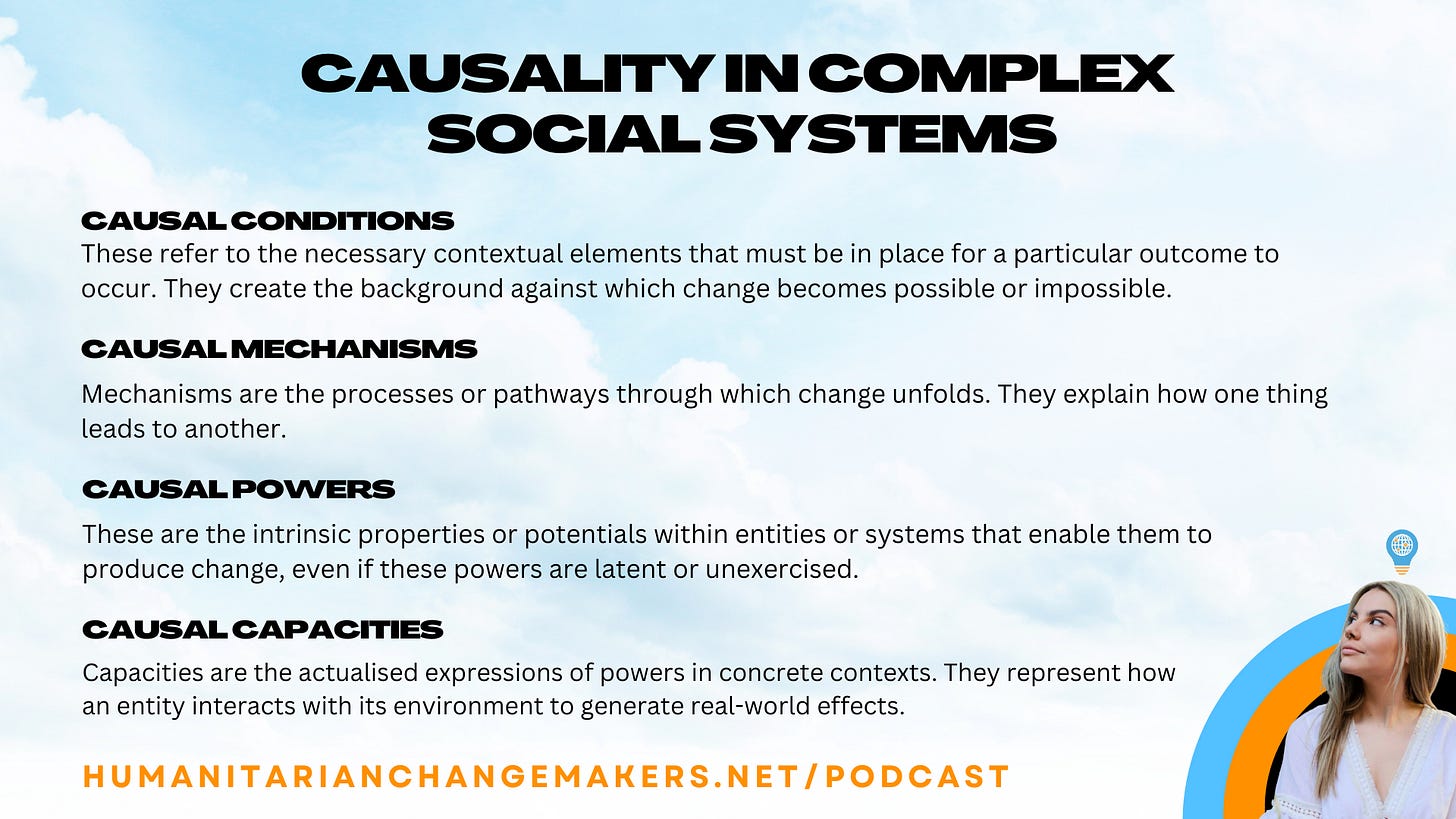

For changemakers across diverse domains — including activism, social enterprise, education, non-profit work, and policy — a sophisticated grasp of causality is essential. It enables practitioners to identify leverage points, anticipate unintended consequences, and design interventions that are contextually sensitive and strategically robust. There are four key dimensions of causal structure: causal conditions, causal mechanisms, causal powers, and causal capacities. Each offers a distinct but interconnected lens through which to understand the dynamics of change in social systems.

1. Causal Conditions: The Contexts That Make Change Possible

Causal conditions refer to the necessary circumstances or contextual factors that must be in place for a change to occur. These are often structural, environmental, or institutional features that form the backdrop against which causal processes unfold. Importantly, causal conditions are not causes in themselves, but rather enabling or constraining factors that allow other causal elements to take effect.

For changemakers, recognising causal conditions is vital for timing interventions, identifying risk, and ensuring that the necessary foundations for change are either present or actively cultivated. It is a reminder that no intervention operates in a vacuum; context matters, often decisively.

2. Causal Mechanisms: The Processes That Drive Change

While causal conditions set the stage, causal mechanisms are the engines that drive change. These refer to the underlying processes or chains of events through which one phenomenon gives rise to another. In essence, mechanisms explain how change happens — the pathways through which inputs become outputs, or actions lead to consequences.

Mechanisms can be psychological (e.g., shifts in belief or motivation), relational (e.g., diffusion of innovation through social networks), institutional (e.g., changes in governance structures), or material (e.g., economic redistribution). They often involve feedback loops, interactions, and emergent properties that cannot be reduced to linear cause-effect relationships.

Identifying causal mechanisms is crucial for designing interventions that are not only evidence-informed but also theoretically coherent.

3. Causal Powers: The Latent Potential for Change

Causal powers refer to the inherent potentials or abilities within entities — whether individuals, institutions, systems, or social norms — to produce change. These powers exist regardless of whether they are currently being exercised. They are dispositional rather than active; that is, they represent what an entity can do, given the right conditions and context.

For changemakers, paying attention to causal powers means looking beyond immediate activity to latent possibilities. It invites questions such as: What capacities are underdeveloped or suppressed? What strengths or traditions remain untapped? Which individuals or groups have unrealised leadership potential? Recognising causal powers helps in building long-term strategies that nurture and activate these latent forces.

4. Causal Capacities: Realising Change Through Interaction

Whereas causal powers represent potential, causal capacities are their realised expression — the actual ability of an entity to generate effects in a given context. Capacities are emergent, relational, and often contingent upon both internal dynamics and external conditions. They reflect how well an entity or system can engage with its environment to produce concrete outcomes.

Understanding causal capacities is critical for changemakers because it speaks directly to questions of effectiveness, resilience, and scalability. It also highlights the importance of building situated capacities — those tailored to specific cultural, political, or ecological contexts — rather than assuming one-size-fits-all models of change.

Integrating Causal Dimensions in Practice

A systems-informed theory of change integrates all four aspects of causality:

Conditions identify what must be in place for change to be feasible.

Mechanisms explain how change occurs through processes.

Powers describe what could happen given the latent potential.

Capacities assess what is happening in actual, context-specific terms.

By attending to all four dimensions, changemakers can move beyond reactive or linear thinking to more nuanced, adaptive strategies that are responsive to complexity, uncertainty, and emergence.

Below are examples of the causal structure of three phenomena—growing a plant, homelessness, and domestic violence—each broken down in terms of their fundamental philosophical properties of causality: causal conditions, causal mechanisms, causal powers, and causal capacities. These examples aim to illuminate the metaphysical structure of causation rather than merely offer empirical correlations or proximate causes. In each case, the examples move beyond surface explanations to illustrate how causality operates at a deeper level of ontology and social reality.

1. Growing a Plant

We often understand plant growth in a straightforward, linear manner: “A seed grows into a plant if it is watered and exposed to sunlight.” This implies a direct cause-effect relationship, where environmental inputs (water, light) are viewed as sufficient causes of growth. The deeper roles of internal plant biology, dormant potential, or environmental interaction are often overlooked.

Contrast: While the conventional view emphasises immediate inputs, the causal structure reveals that growth depends on a seed’s latent biological powers, the environmental conditions that enable these to be activated, and the mechanisms through which development unfolds.

Causal Conditions: These include the environmental circumstances necessary for plant growth—adequate sunlight, fertile soil, access to water, and appropriate temperature. These conditions are not causes in themselves but provide the context in which causes can be activated. Without these, growth is impossible, regardless of the presence of other factors.

Causal Mechanisms: These refer to the biological and biochemical processes by which growth occurs—photosynthesis, cellular respiration, nutrient uptake, and gene expression. Mechanisms explain how causal powers bring about the effect (growth), describing the unfolding of processes over time.

Causal Powers: These are the intrinsic capacities of the seed itself, including its genetic potential to develop into a particular kind of plant. These powers exist even in dormant seeds and are not contingent on whether they are exercised. The seed contains the form and function of the plant in potentia.

Causal Capacities: These are the realised expressions of the seed’s powers under the right conditions—when the seed germinates, develops roots, stems, and leaves. Capacities demonstrate what the plant is able to do in interaction with its environment, illustrating the interface between internal power and external condition.

2. Homelessness

A common causal narrative about homelessness focuses on individual deficits: “A person becomes homeless because they lost their job or have an addiction” or simply that “they don’t have permanent housing.” This frames homelessness as the result of discrete, personal events, often ignoring broader systemic and structural factors.

Contrast: The causal structure approach highlights how homelessness arises from the interplay between social conditions (e.g., housing markets, welfare systems), institutional mechanisms (e.g., discharge from care), and the latent powers of exclusion or support embedded in policy and infrastructure.

Causal Conditions: These include structural and systemic features of society—such as the availability of affordable housing, employment conditions, health services, and legal protections. They constitute the broader social, economic, and policy environment that sets the stage for whether homelessness becomes a likely outcome.

Causal Mechanisms: These involve the social, psychological, and institutional pathways through which individuals become homeless. Mechanisms may include eviction processes, the breakdown of family networks, institutional discharge without support (from prisons or hospitals), or trauma and mental health deterioration. These mechanisms mediate how societal structures are translated into lived experience.

Causal Powers: In this context, causal powers might reside in institutions (e.g., markets, governments, legal systems) and social norms that have the latent capacity to include or exclude, protect or marginalise. These powers are not always visible or exercised, but they shape the conditions of possibility for housing security.

Causal Capacities: These manifest when the latent powers of social systems are activated. For example, a housing market that lacks regulation may exercise its capacity to price people out of shelter, or punitive welfare systems may exercise their capacity to disqualify those in need. At the individual level, capacities may refer to a person’s ability to navigate bureaucracies, access support, or maintain employment—capacities shaped by social and institutional design.

3. Domestic Violence

In popular discourse, domestic violence is often attributed to immediate triggers: “An abusive person lashes out in anger due to stress or substance use.” This view isolates violence to episodic, individual choices, and often implies personal moral failing or lack of self-control.

Contrast: A structural causal lens reveals how violence emerges from embedded social powers (e.g., patriarchy), facilitated through mechanisms like coercive control and economic dependency. These interact with deep causal conditions and reproduce violence in ways that go beyond individual intent.

Causal Conditions: These may include socio-cultural norms that reinforce gender hierarchies, histories of interpersonal trauma, economic dependency, or isolation from support networks. Such conditions make domestic violence more likely to occur and more difficult to escape. They create the social space in which violence is possible and, at times, tolerated or minimised.

Causal Mechanisms: Mechanisms might include patterns of coercive control, cycles of abuse, power imbalances, and emotional manipulation. These processes explain how violence is enacted and maintained, how it escalates, and how it systematically undermines the agency of the victim.

Causal Powers: Here, causal powers may lie in the individual psychology of the perpetrator (such as tendencies toward control or aggression), but more fundamentally, in the social institutions and norms that confer asymmetrical power relations—especially those linked to gender, race, and class. These powers persist regardless of whether they are being exercised in any given moment.

Causal Capacities: Capacities are the concrete realisation of these powers—for instance, when an abusive partner exercises control through economic restriction, threats, or physical violence. The capacity for harm is shaped not only by individual intent but also by the systemic enablers that protect abusers and silence victims (e.g., lack of legal recourse, inadequate shelter systems, or stigma).

By distinguishing between causal conditions, mechanisms, powers, and capacities, we gain a more philosophically rigorous and analytically useful understanding of causality. This approach moves beyond surface-level explanations and helps changemakers, researchers, and theorists to identify where and how interventions can be most effectively targeted—whether in seeding social transformation, reshaping institutional dynamics, or disrupting harmful systems of power.