3 Valuable Systems-Thinking Tools for Social Changemakers

019. Applying Systems-Thinking Tools to the LA Fires

In addressing complex social and environmental challenges, social changemakers benefit immensely from systems-thinking tools that enable nuanced understanding and intervention design. Three critical tools—systems mapping, the iceberg model, and causal loop diagrams—offer unique and complementary perspectives for navigating the intricacies of social systems. By exploring their applications and implications, we can uncover how these tools empower changemakers to foster systemic change.

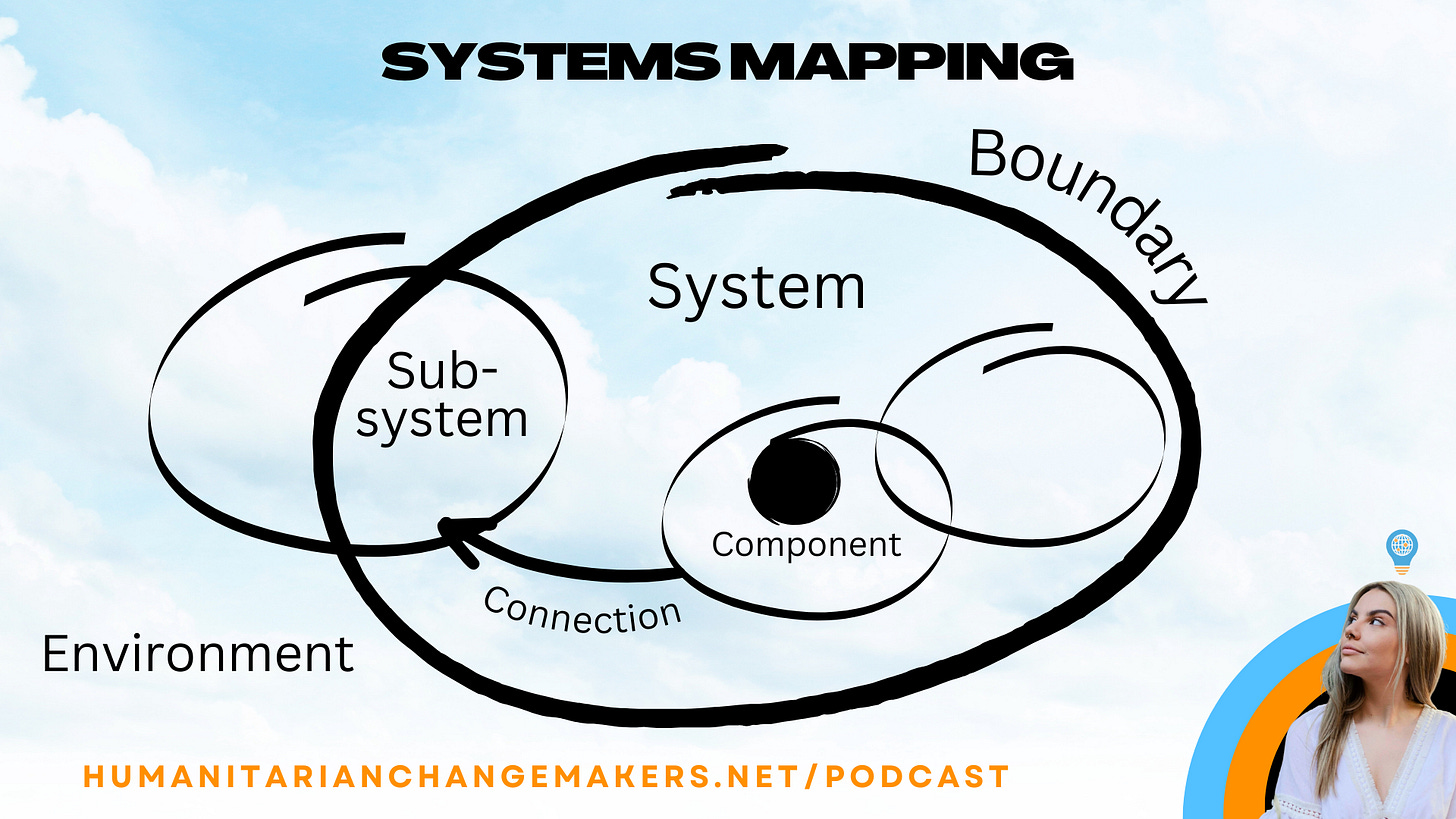

Systems Mapping: Navigating Complex Systems

Systems mapping is an essential tool that provides an overview of a system's components, their interrelationships, and the broader ecosystem within which they operate. The process begins with defining a boundary to separate the system from its environment, though in soft or critical systems thinking, boundaries remain flexible to accommodate the complexity of social systems.

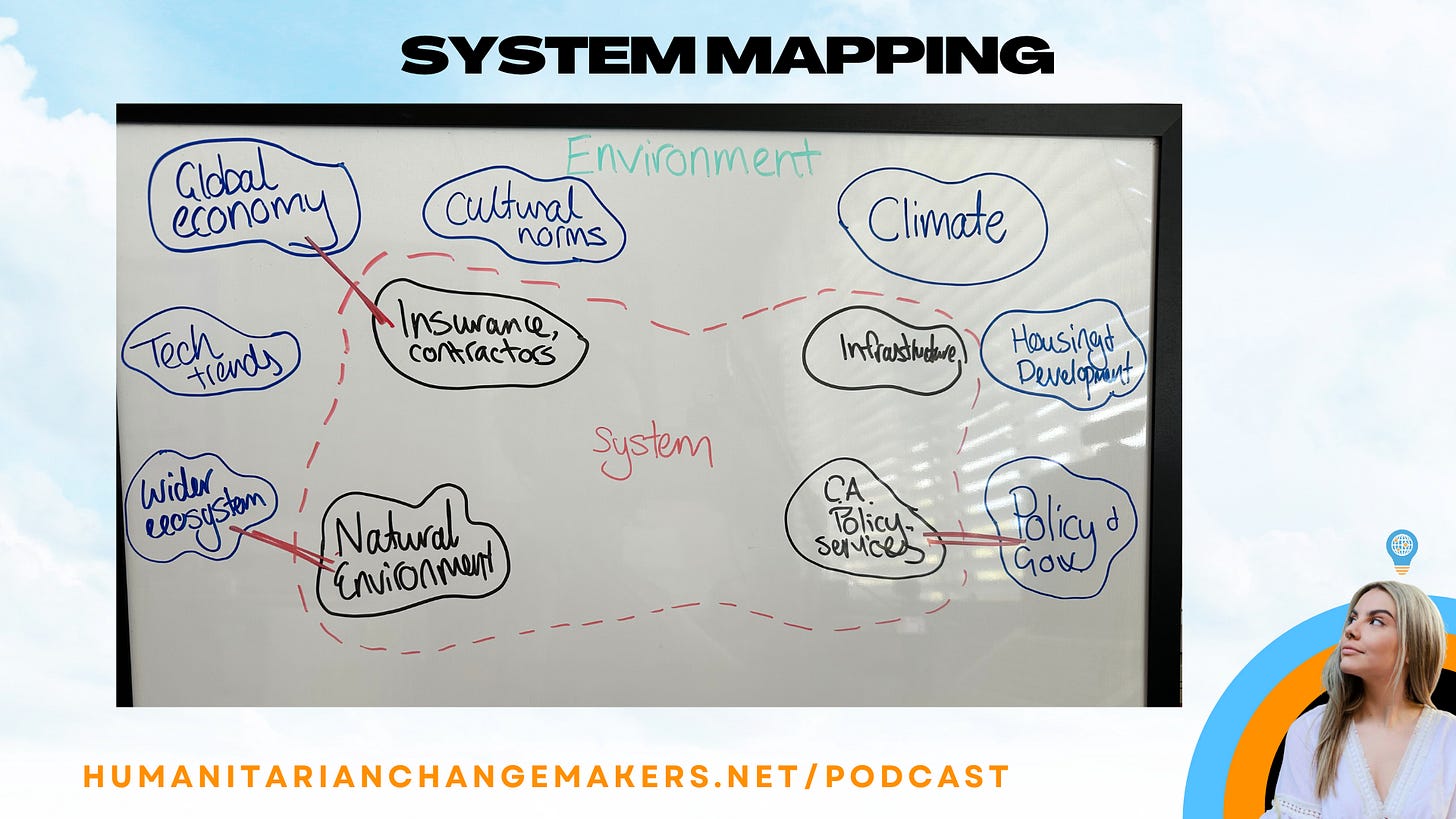

For instance, when analysing the Los Angeles (LA) wildfires, systems mapping helps delineate key components such as the natural environment (e.g., eucalyptus trees, soil, water resources), social systems (e.g., residents, public and private firefighters, homeless populations), and infrastructure (e.g., housing developments, transportation networks). The mapping process also identifies external factors such as global climate change, federal policies, and international markets that influence the system but operate outside its boundary.

A critical feature of systems mapping is its capacity to visualise feedback loops and flows of energy, information, or resources between components. For example, eucalyptus trees, imported from Australia, exacerbate fire intensity due to their high flammability. Concurrently, socio-economic inequalities, such as access to private firefighting resources, deepen the crisis, highlighting structural vulnerabilities. These insights enable changemakers to identify leverage points for intervention, such as advocating for equitable resource distribution or revising land-use policies.

Systems mapping offers a "lay of the land," akin to a physical map. While it does not delve into specific causal relationships or behavioural patterns, it establishes a foundation for further analysis, making it an indispensable preliminary step in systems thinking.

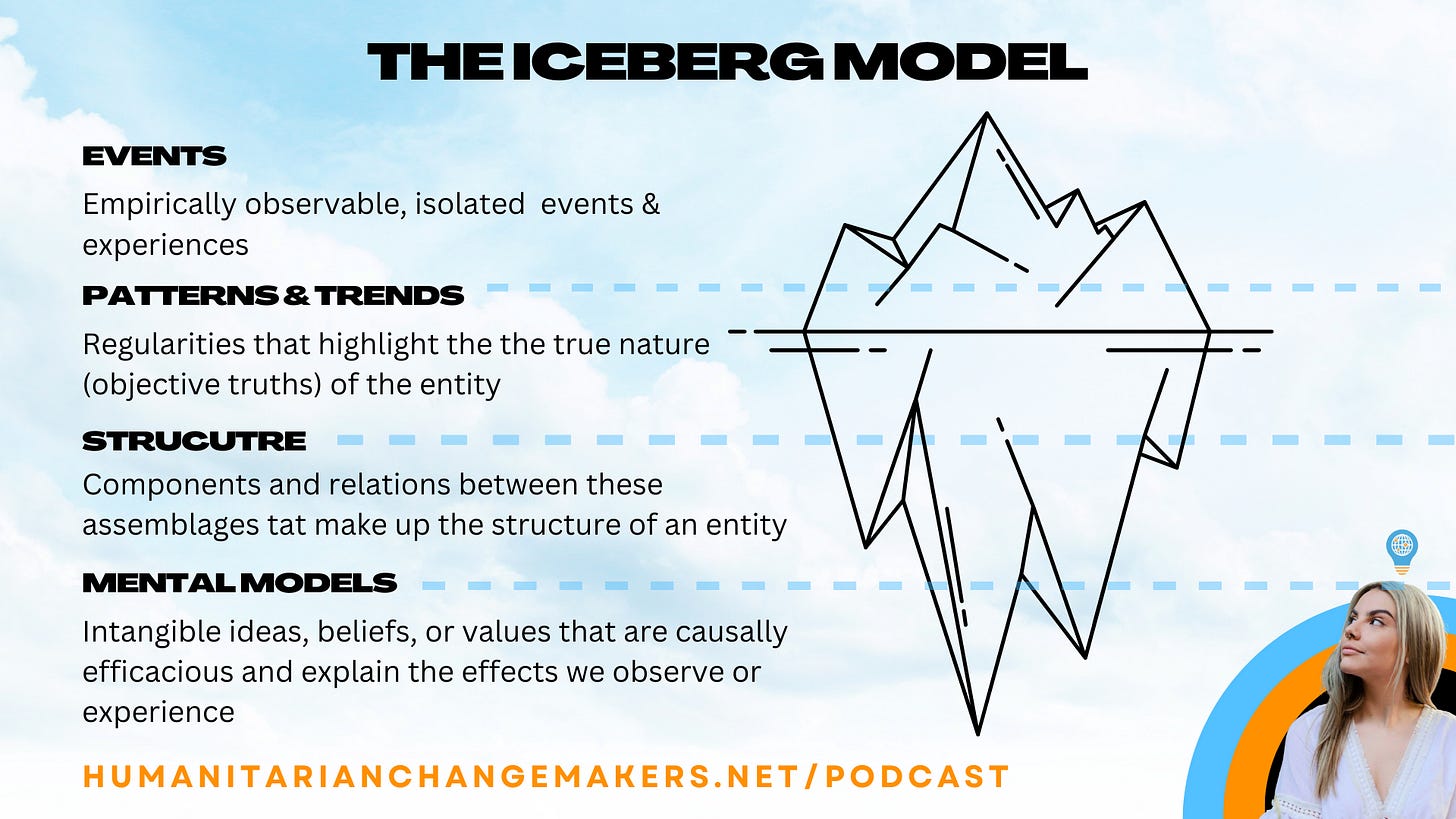

The Iceberg Model: Uncovering Root Causes

The iceberg model builds on systems mapping by revealing the underlying structures and mental models driving observable events and patterns. It is based on the analogy that most of an iceberg lies hidden beneath the surface, much like the systemic and cultural factors underlying visible phenomena.

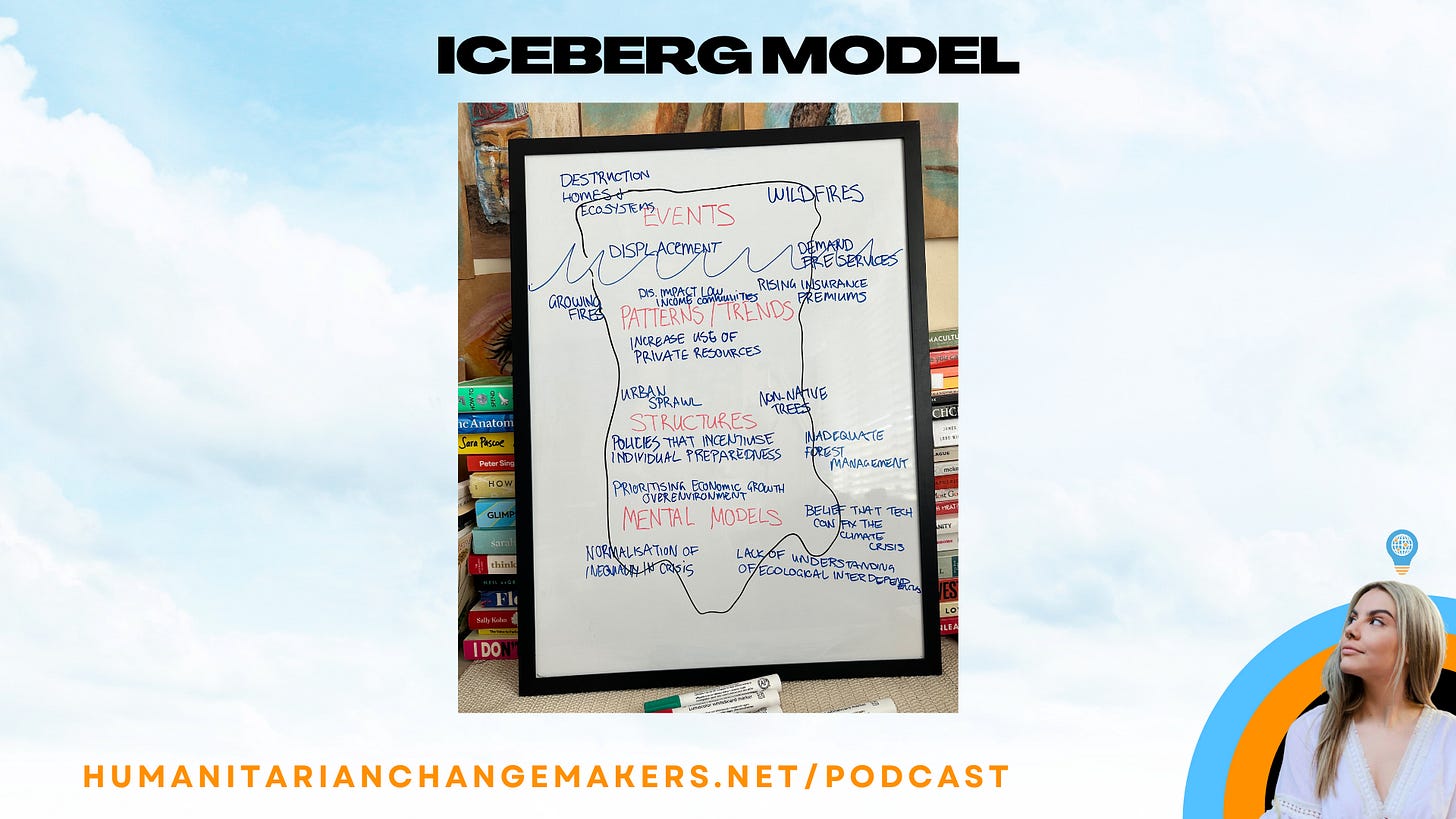

Events represent the tip of the iceberg and include observable occurrences, such as the outbreak of wildfires in LA.

Patterns and Trends lie just below the surface, illustrating recurring phenomena, such as the increasing frequency and severity of wildfires over recent years.

Structures delve deeper, exposing systemic causes such as urban sprawl, privatised water services, and insufficient public firefighting resources.

Mental Models form the base, representing the cultural beliefs and norms that uphold these structures, such as individualism and the prioritisation of economic growth over community resilience.

By applying the iceberg model to the LA wildfires, changemakers can move beyond addressing surface-level events to tackling systemic issues and cultural mindsets. For example, advocating for community-driven fire management strategies requires shifting mental models from individual self-reliance to collective resilience. The model’s layered approach ensures that interventions are grounded in a thorough understanding of the system’s dynamics, increasing the likelihood of sustainable change.

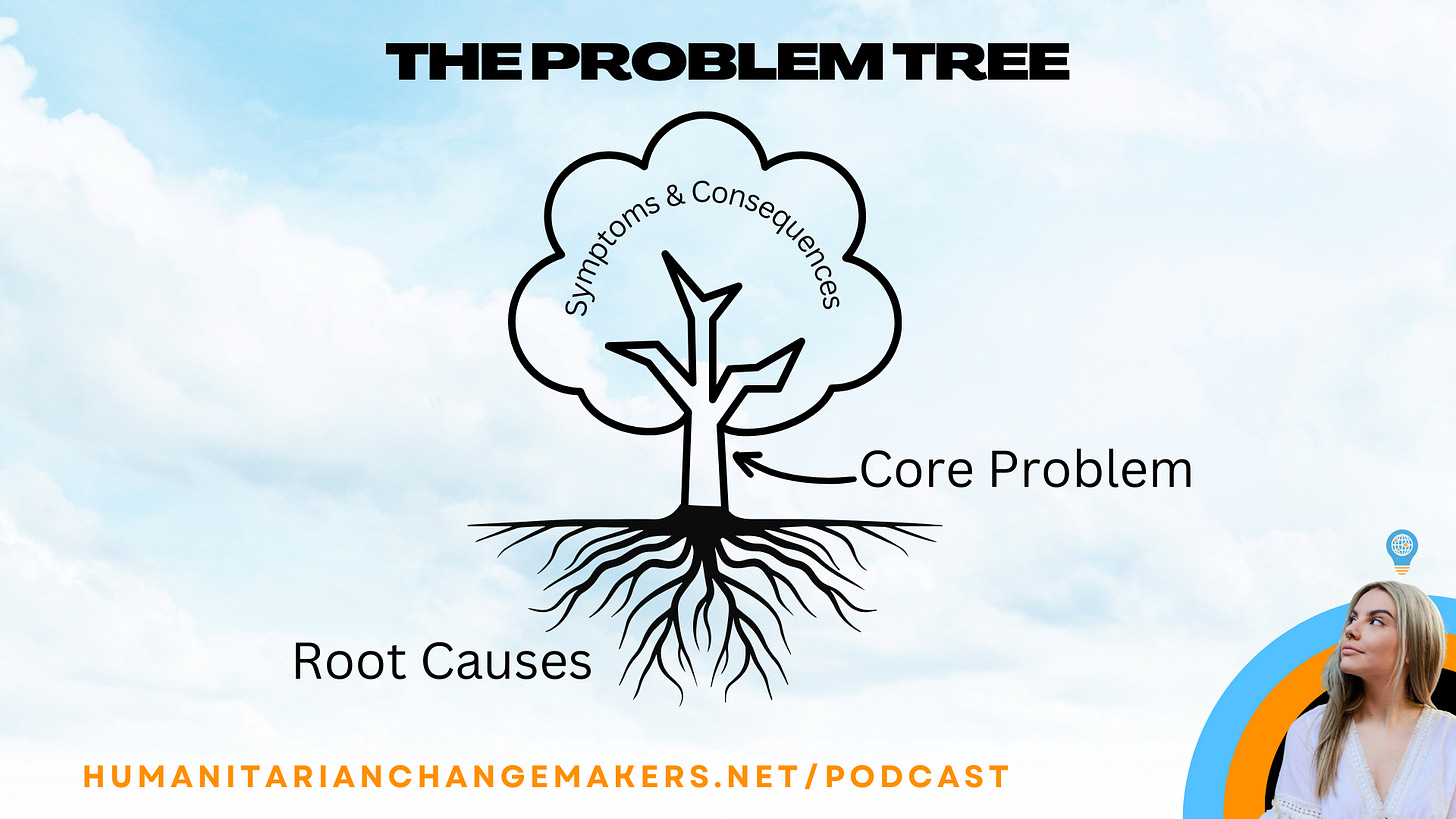

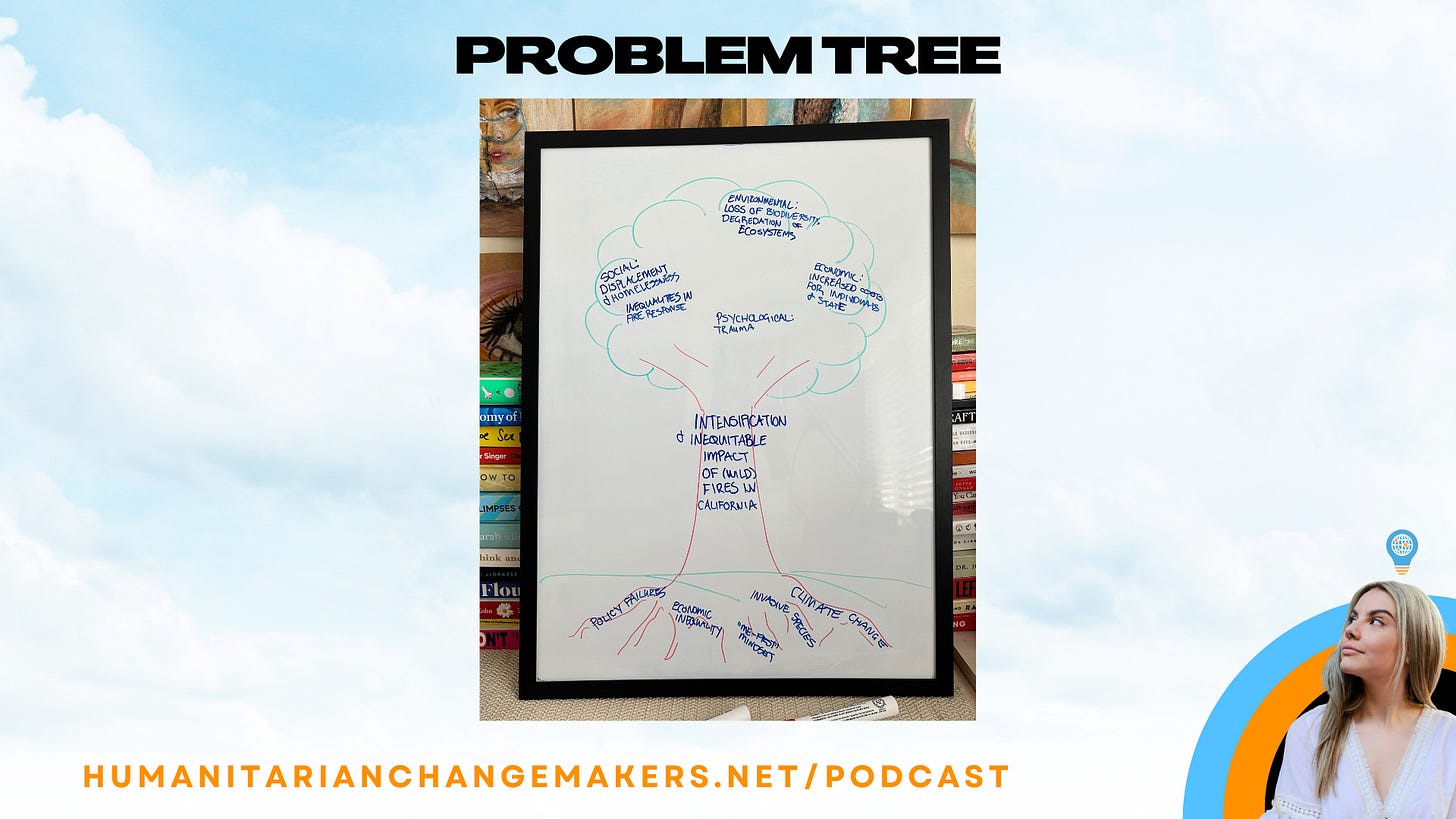

The Problem Tree: Tracing Causes and Consequences

The problem tree is a straightforward yet effective tool for visually mapping the root causes and consequences of an issue. It is structured around three components:

The Trunk: Represents the core problem or issue, such as the increasing intensity and frequency of wildfires in California.

The Roots: Represent the underlying causes of the problem, which can include environmental degradation, policy failures, socio-economic inequalities, or inadequate infrastructure.

The Branches and Leaves: Represent the effects or consequences of the problem, such as loss of homes, displacement, and ecological destruction.

This tool helps changemakers break down a complex issue into manageable components by tracing causal pathways and linking immediate effects to their root causes. For example, a problem tree for the California wildfires might identify poor land management practices, climate change, and economic pressures as root causes, while the consequences could include homelessness, loss of biodiversity, and strain on public resources.

What makes the problem tree particularly useful is its ability to engage stakeholders in a collaborative analysis of the issue. By visually representing the problem, its causes, and its effects, it encourages diverse groups to develop a shared understanding of the challenges and opportunities for intervention. Stakeholders can work together to address root causes, propose preventative measures, or mitigate the consequences.

Practical Applications for Social Changemakers

These tools can be applied in three key ways:

Exploratory Analysis: Systems mapping, the iceberg model, and the problem tree are effective for making sense of complex information and framing issues. For example, the iceberg model can be used to explore the cultural assumptions driving inequities, while systems mapping can clarify the relationships between social, economic, and environmental factors.

Research and Data Analysis: In more formal academic contexts, these tools can guide qualitative and quantitative research. The iceberg model can be used to code qualitative data, as it helps identify recurring patterns, structural factors, and cultural narratives within focus group discussions or interviews.

Collaborative Problem-Solving: These tools foster dialogue and cooperation among stakeholders. For example, systems mapping can help grassroots changemakers, policymakers, and residents co-develop interventions by clarifying roles and responsibilities. Similarly, the problem tree can support workshops aimed at identifying shared priorities and solutions.

Systems thinking tools are indispensable for social changemakers navigating complex challenges. Systems mapping offers a foundational overview of interconnected components, the iceberg model facilitates deeper analysis of systemic causes and mental models, and the problem tree visualises root causes and consequences to inform targeted interventions. Together, these tools empower changemakers to approach problems holistically, ensuring that their efforts are both comprehensive and impactful. By applying systems thinking in their work, changemakers can drive meaningful, sustainable change in the face of pressing global issues.