Navigating the Complexity of Reality: Subjective and Objective Knowledge in Research and Social Change

014. We're answering Dess, an industrial hygienist who was unsure of how researchers tackle more 'subjective' phenomena

In this episode of Changemaker Q&A, we tackle a question that was asked by Dess, an industrial hygienist who was unsure of how researchers tackle more 'subjective' phenomena; "how can you do a PhD on a topic soooo subjective… as an Industrial Hygienist have to read so many scientific articles from research and a lot are so inconclusive basically *use at your own risk, *needs more research, etc. can't imagine research about a word like empowerment." This is a common question I get asked as a social researcher, which opens the door to a broader discussion about the often overlooked philosophical foundations of research and the need to embrace both the subjective and objective aspects of knowledge, and avoid many of the dualisms we see in contemporary Western thinking.

Misconceptions about "Subjectivity"

Addressing Des's concerns about inconclusive research, I highlight that inconclusivity often stems from methodological challenges rather than being inherently linked to subjectivity or objectivity. Methodological issues such as sample size, study design, and data analysis can compromise reliability and validity, leading to ambiguous results in both subjective and objective research.

What people tend to consider ‘subjective’ is probably better understood as being context-dependent. Dess mentioned ‘inconclusive’ results, this is probably more-so the challenge of the results only being applicable in a certain context, not being subjective ‘open to individual interpretations or experiences.’ Context dependency doesn't diminish the validity of research findings.

We often think that ‘conclusive’ research can’t be open to re-interpretation or correction, but thats the very nature of knowledge is that it evolves as humanity does. That's why it's so important to have researchers that play different roles in the building of knowledge.

The Puzzle Analogy

There's a quote that summarises the basis for so many of these misconceptions we have;

“We've moved from wisdom to knowledge, and now we're moving from knowledge to information, and that information is so partial – that we're creating incomplete human beings”

— Vandana Shiva

Ever since Descartes, Western thinkers have thought about the world in terms of differences and 'split' reality into dualisms; macro vs micro, theory vs practice, subjective vs objective. But these dualisms are a misinterpretation of the duality of reality. They aren’t opposing phenomena or ways of viewing the world, they are two sides of the same coin, and their existence is intrinsically connected to and dependent on the other. We must get past this need to create false dualisms about reality, and begin to understand things more holistically.

In the puzzle analogy, I propose that researchers play three distinct roles in building a more holistic body of knowledge about phenomena— focusing on individual puzzle pieces, putting pieces together to identify patterns and trends, and examining the entire puzzle. These roles allow for a nuanced understanding that transcends dualistic thinking and provides a more holistic view of how knowledge is constructed to provide a more robust understanding of reality.

There are lots of phenomena that individuals experience subjectively — psychology, finance/economics, politics, ethics, justice, history — yet while people have subjective views or experiences of these things, or behave in a way that is dependent on a certain context, we can still study them objectively.

Take health for example, where people have their own ideas about what health means to them, what they believe is healthy, and how they approach health— but we can still research health objectively. We can develop certain indicators, standards, and approaches to health based on objective analysis, while also considering the subjective experiences individuals may have. It’s possible to have both. We develop this well-rounded understanding of health by ensuring we have researchers that take this different approaches to their research, allowing us to build a comprehensive understanding of health.

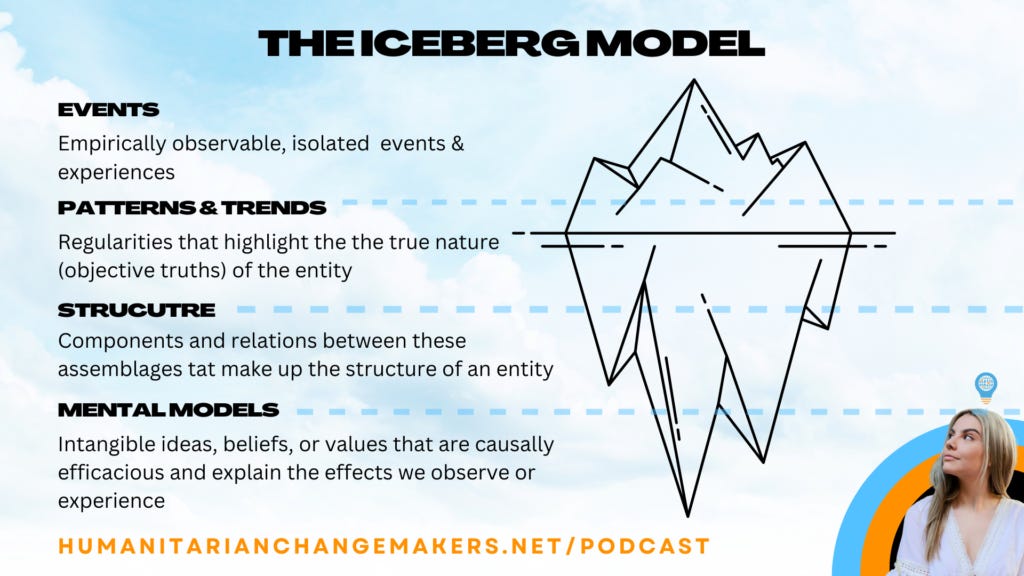

The Iceberg Model

Drawing on systems thinking, the iceberg model as a heuristic tool that we can all use to navigate complex phenomena. The iceberg model offers as a practical tool for researchers and practitioners to approach their work with a holistic perspective, acknowledging the intricacies of reality.

We can’t reduce reality to the subjective/contextual/relative perspectives, nor should we reduce it to the objective/empirical facts that we can observe. We need to go deeper than that, and take a holistic view that includes all of these levels of the iceberg.

The visible tip of the iceberg represents empirical knowledge—observable events and experiences, including both subjective interpretations and measurable, objective data. This top layer offers a starting point for exploration.

Moving beneath the surface, the model delves into patterns and trends. Here, changemakers can identify recurring themes and commonalities, recognising broader trends that transcend individual experiences. This layer invites exploration into the relationships between various events, bridging the subjective with observable patterns.

Further down lies the layer of underlying structures. Changemakers can examine social relations, policies, cultural norms, or systemic frameworks that underpin observed patterns. Understanding these structures provides insights into the foundations influencing observed phenomena, integrating both subjective and objective aspects.

Lastly, the deepest layer encompasses mental models—beliefs, values, ideologies—that drive behaviours and shape societal norms. This layer forms the core of subjectivity, representing the intangible aspects that influence individual and collective experiences, adding depth to the understanding of observed phenomena.

For a changemaker, utilising the iceberg model involves peeling back layers systematically. By analysing empirical data, identifying recurring patterns, understanding systemic structures, and delving into underlying mental models, a holistic comprehension of a phenomenon emerges, that encompasses both the subjective and objective perspectives. This comprehensive approach enables changemakers to appreciate the interplay between subjective and objective elements, fostering a deeper understanding crucial for driving effective and sustainable change.

Listen to the full episode:

It's interesting that regardless of the field, regardless of the discipline, a Ph.D. is a philosophy doctorate, yet researchers rarely question the underlying philosophical assumptions shaping how they build knowledge... let's not make the same mistake as changemakers!

Click here to read the full episode transcript.